Porella japonica (Sande Lacoste) Mitten subsp. appalachiana R.M. Schuster

Family: Porellaceae

Synonyms

none

NatureServe Conservation Status

G5? T1

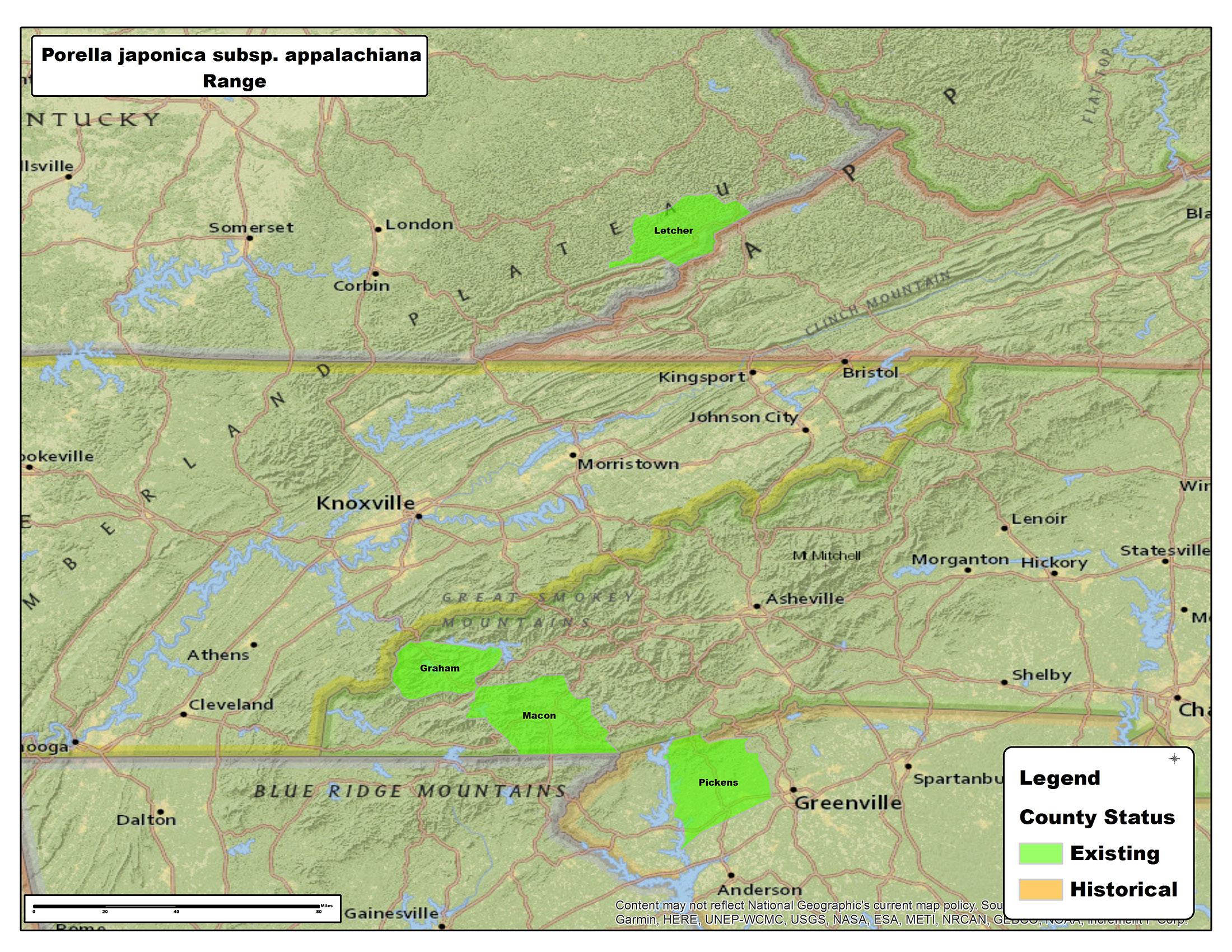

Distribution

Endemic to southeastern U.S.A. Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina. The record from China (Jia et al. 2016) is probably mistaken (see Bakalin 2018).

Habitat

In mixed hardwood forests often with Tsuga canadensis. On rock and mosses over rock, rarely spreading to bark of vascular plants adherent to rock. Shaded, “hardly damp,” vertical faces of large boulders in stream ravine (Type locality in Pickens Co., S.C.); north facing rock bluff in splash zone of drip water; on “dry” vertical rock somewhat exposed and a few feet from running water and under the influence of cool air drainage from deep rock crevices; shaded, moist rock in vicinity of rockhouse and nearby creek. Moderate elevations (1000 – 3500 ft)

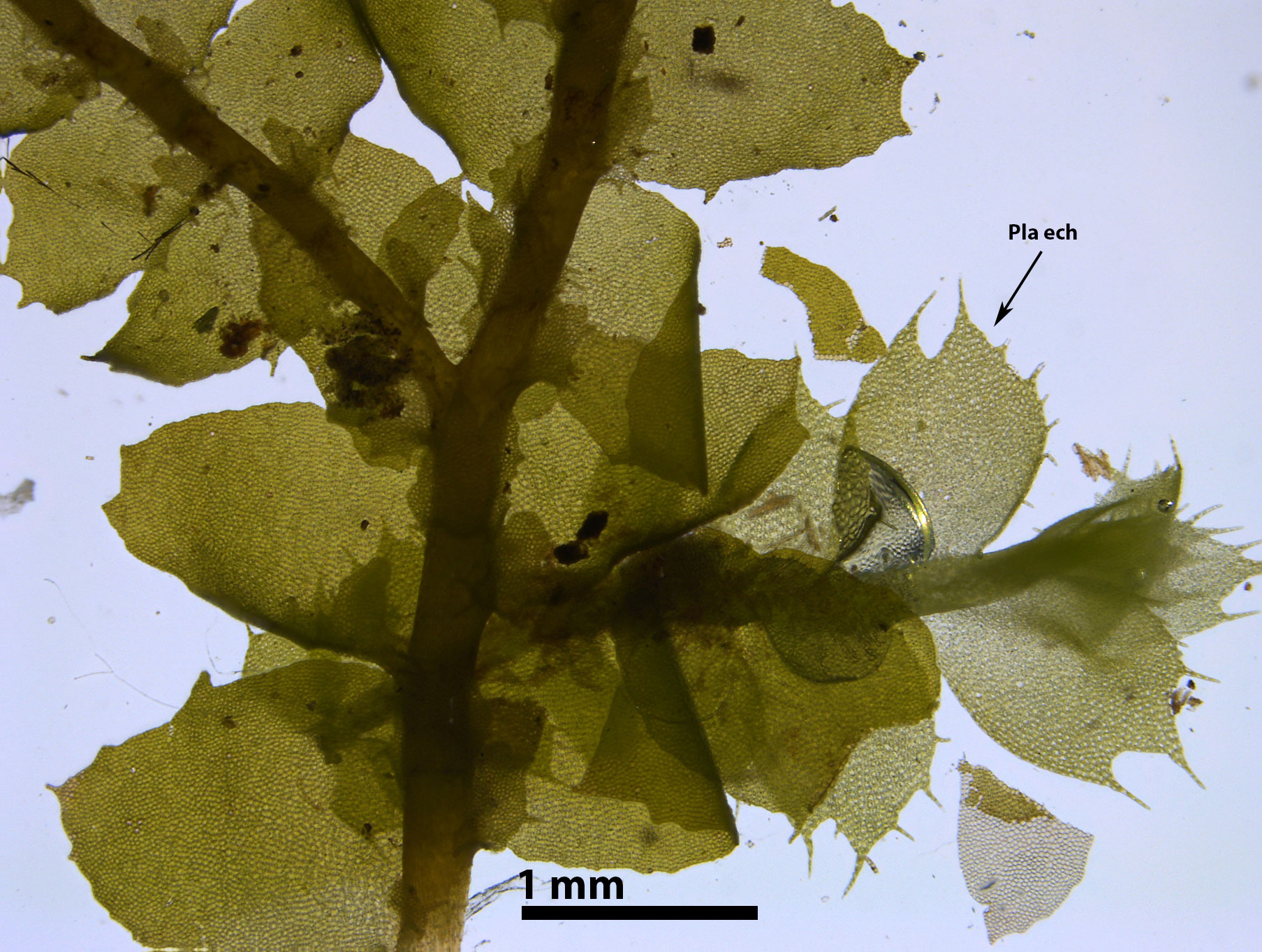

Associated liverwort species include Cololejeunea biddlecomiae, C. ornata, Frullania plana, Plagiochila appalachiana, P. echinata, P. virginica, Radula voluta (Schuster 1980); Herbertus tenuis, Radula mollis, and R. obconica (Davison and Risk 1992). A population in Graham Co., N.C., whose phenotype rivals the type specimen illustrated by Schuster (1980, fig. 639), occurred with Cololejeunea biddlecomiae, Frullania plana, Lejeunea laetivirens, Lejeunea sharpii, Plagiochila echinata, Porella pinnata, Radula voluta, and the filmy fern Trichomanes petersii.

Brief Description and Tips for Identification

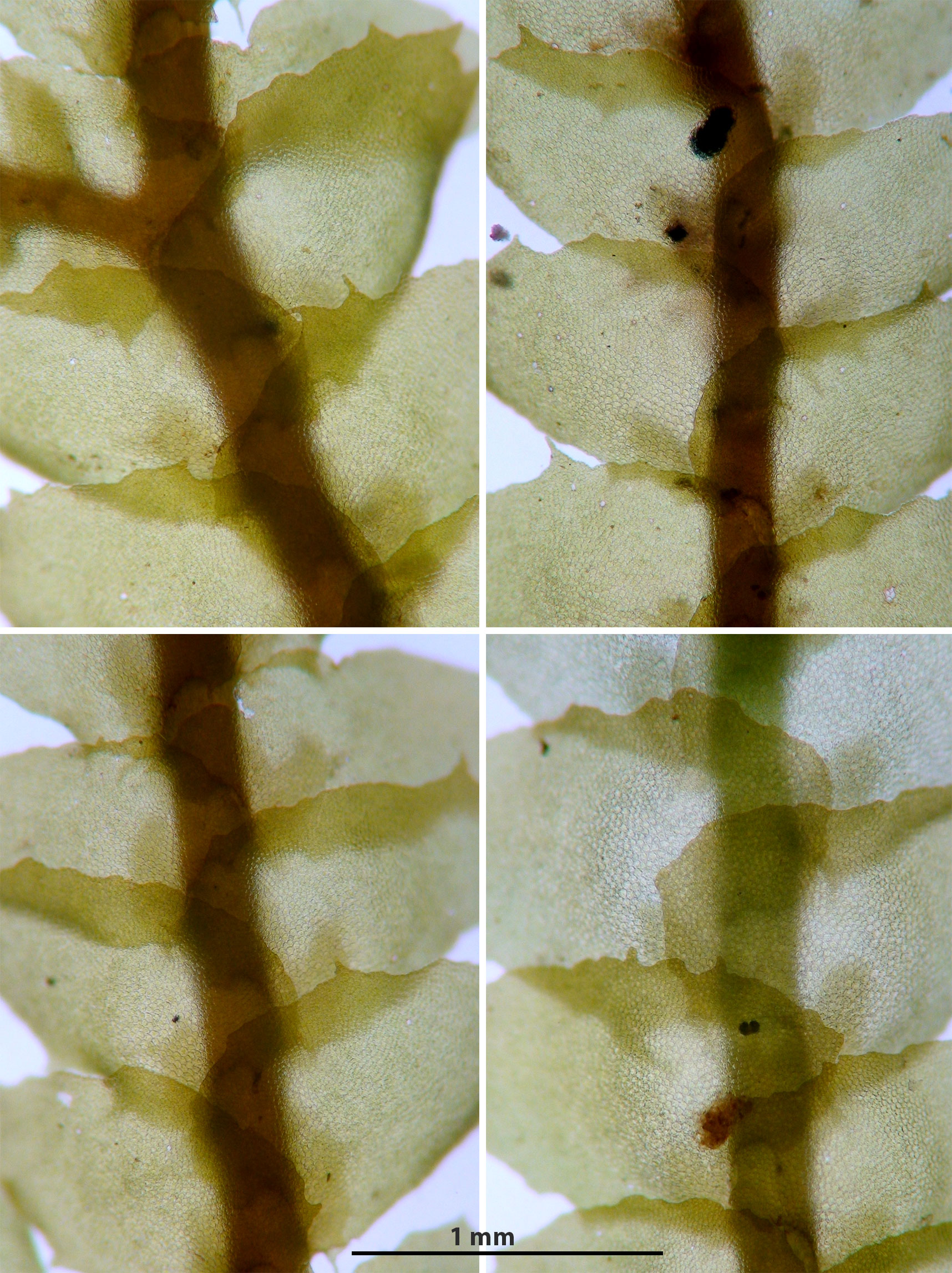

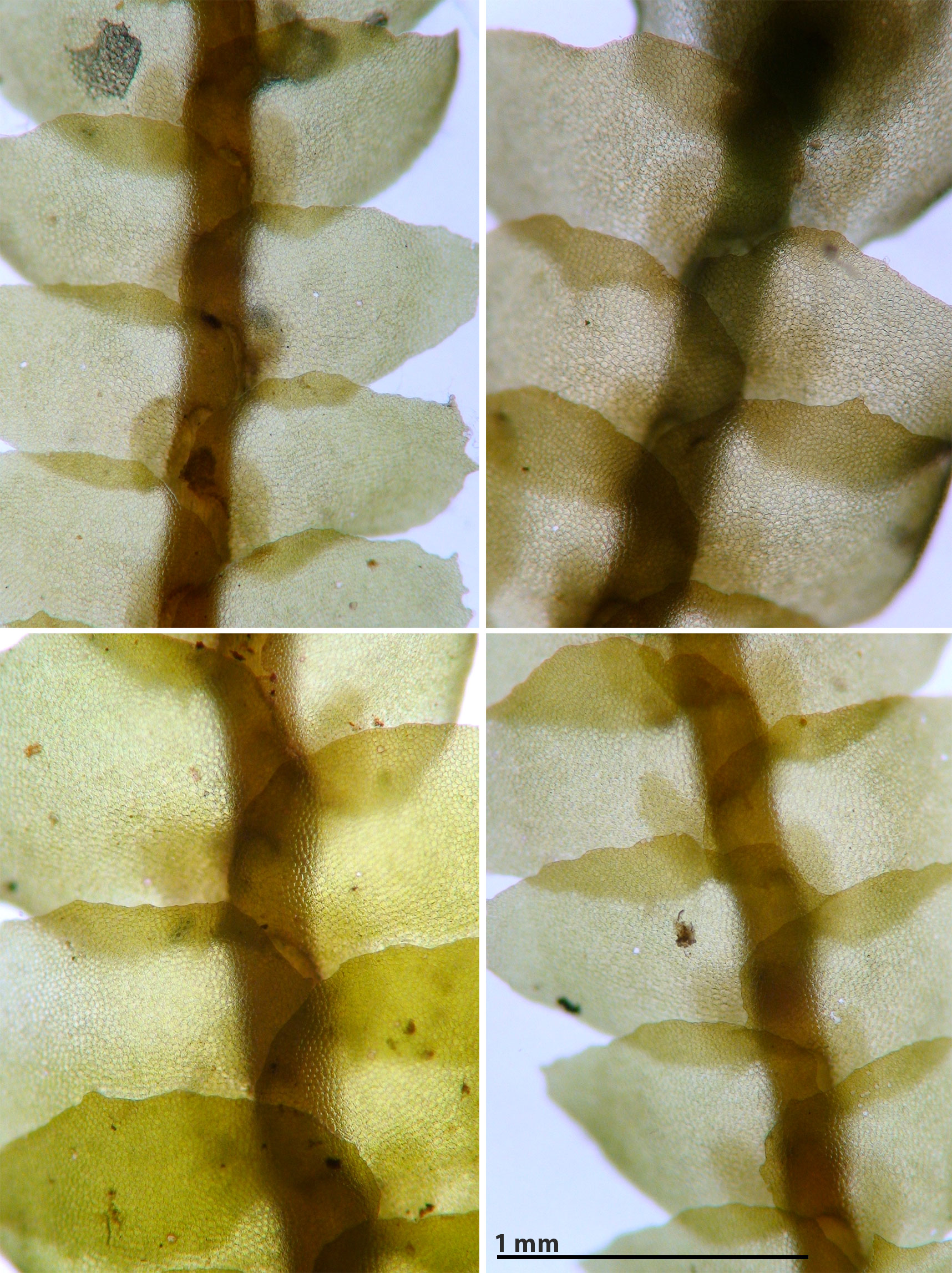

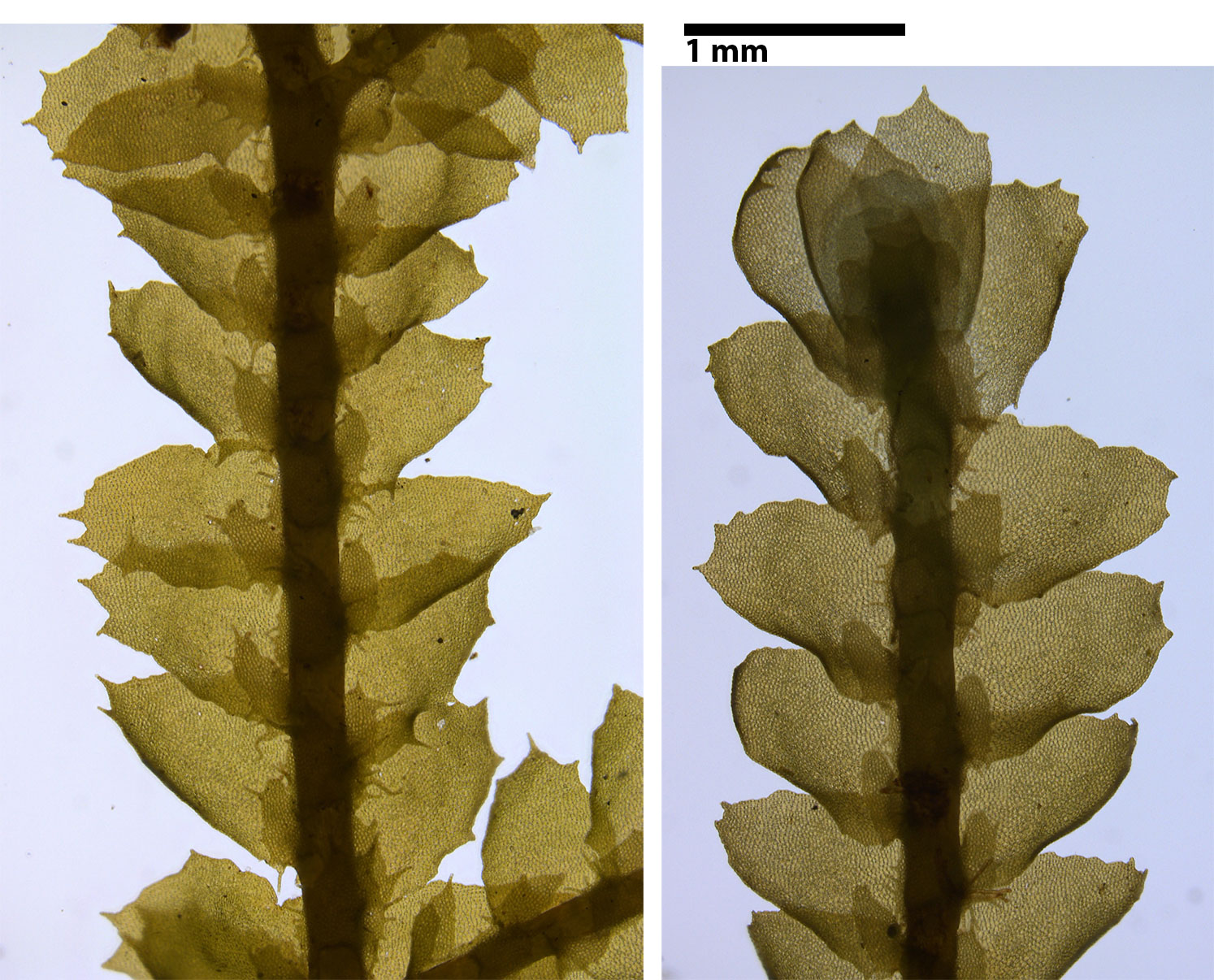

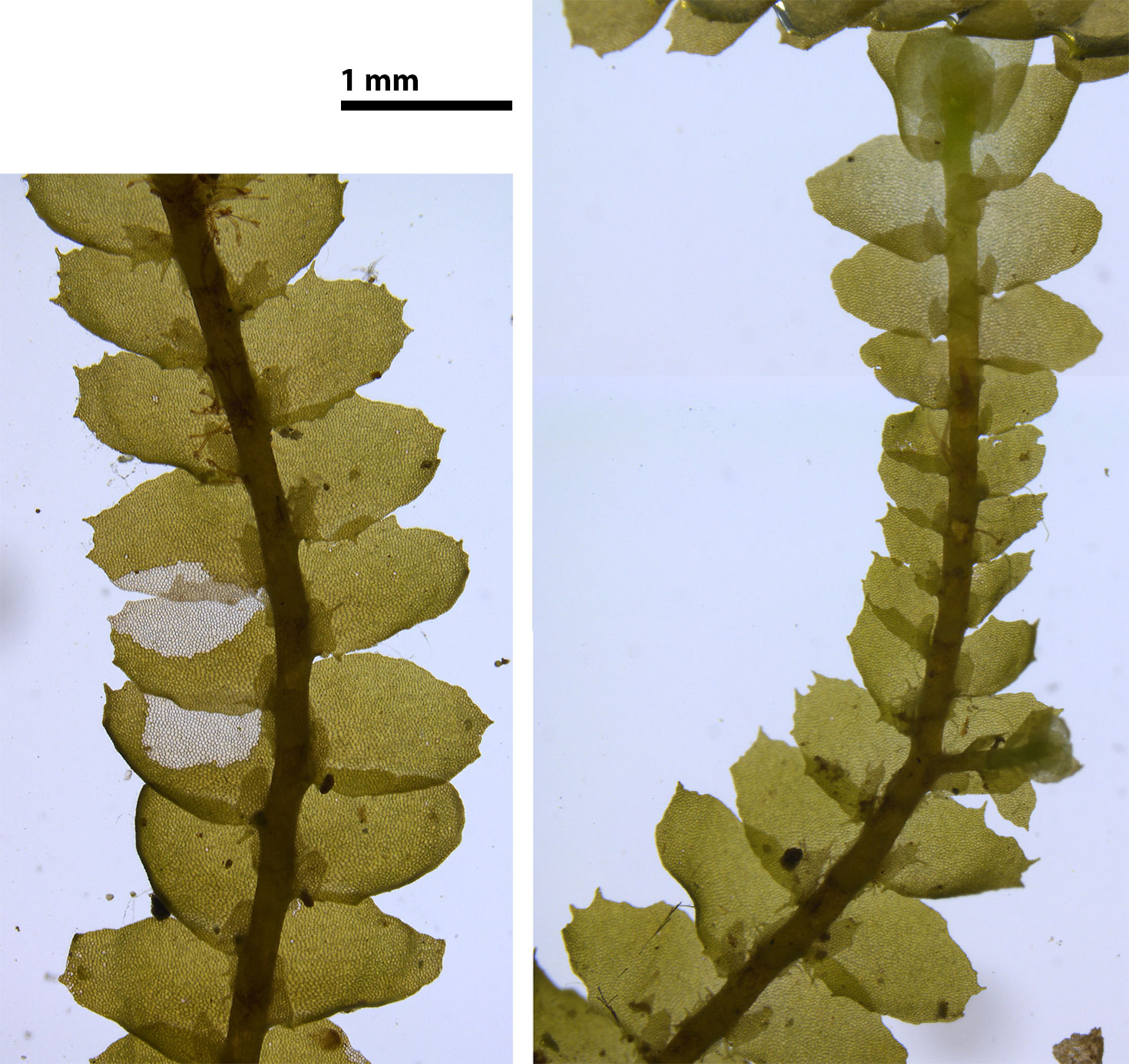

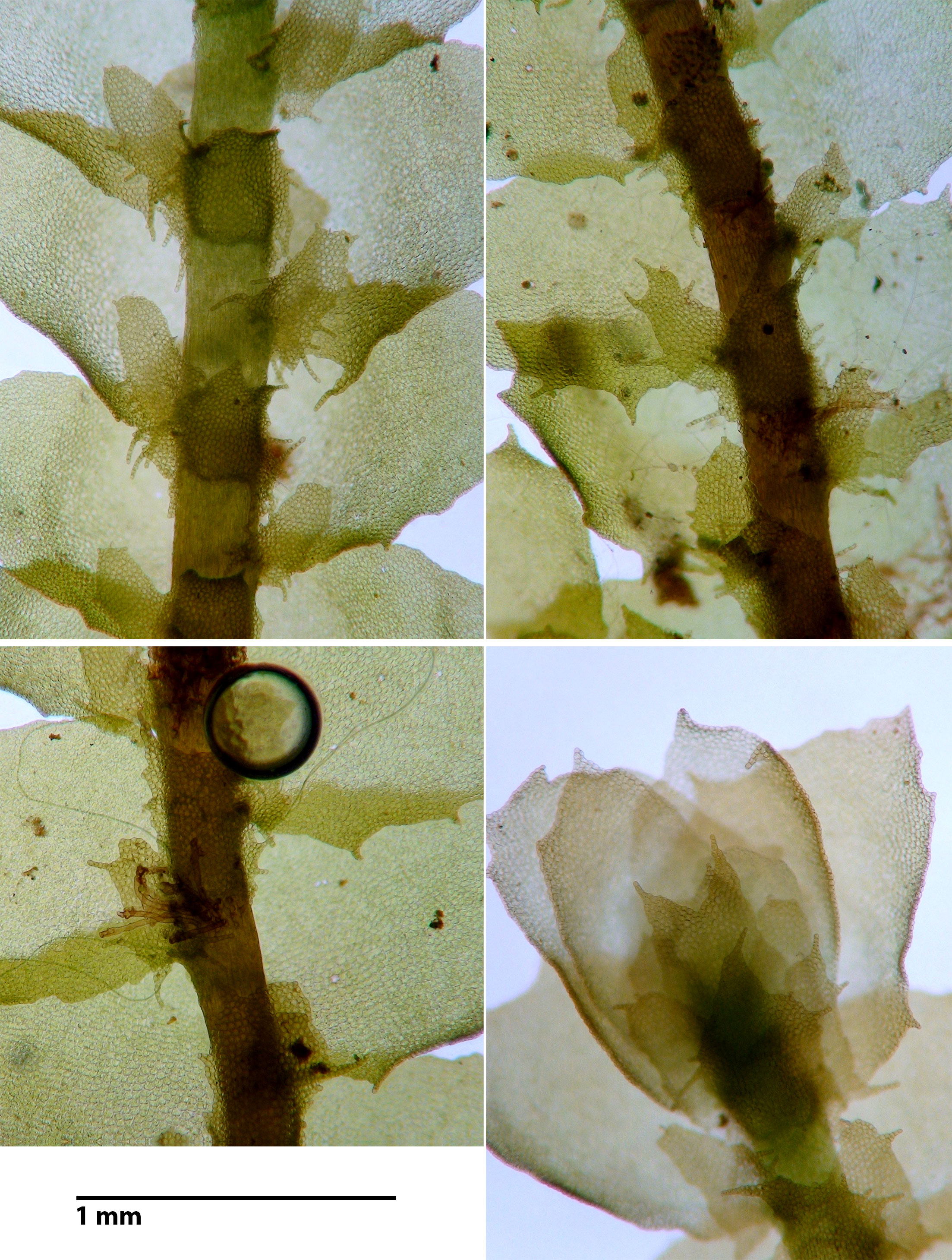

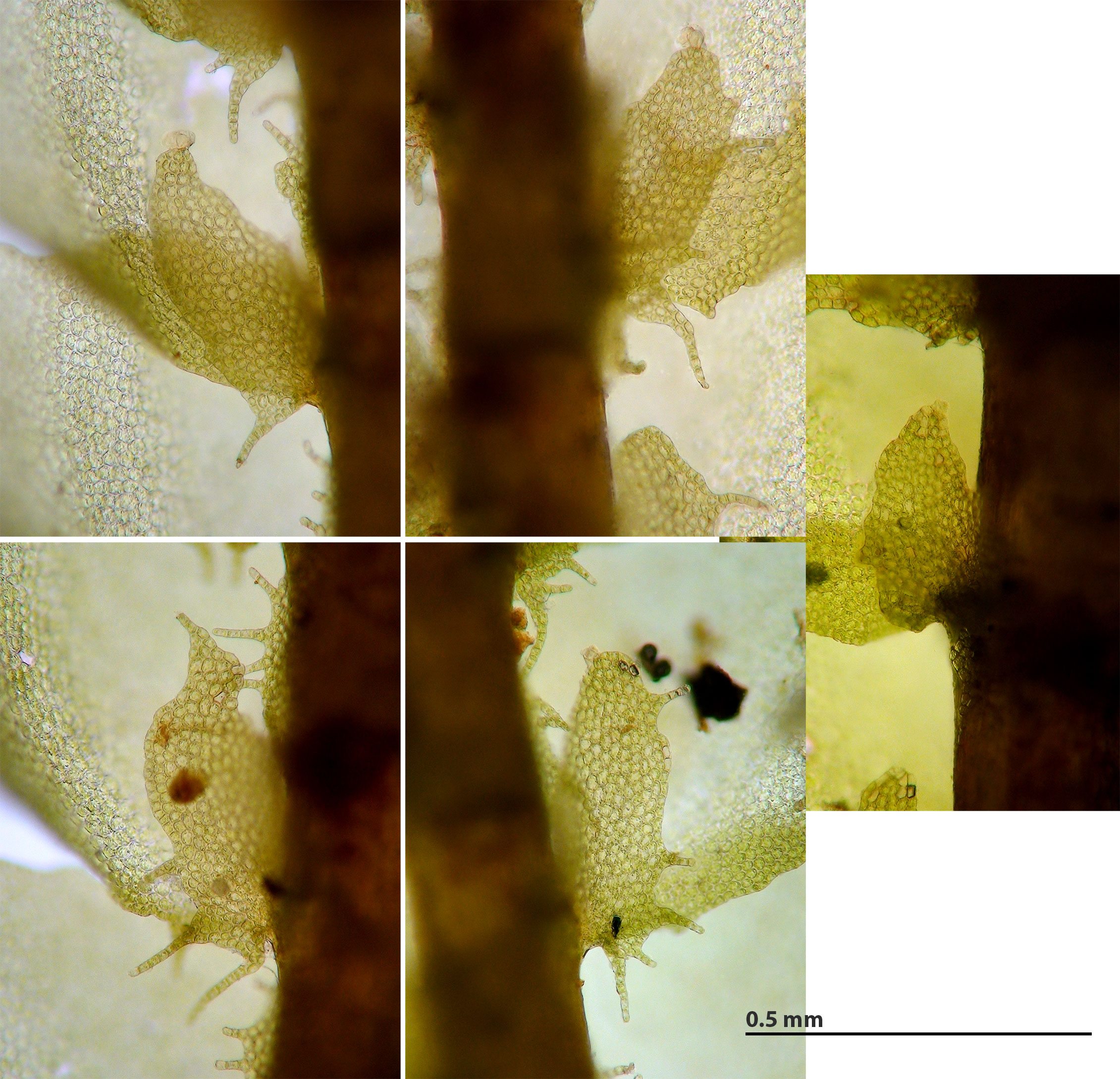

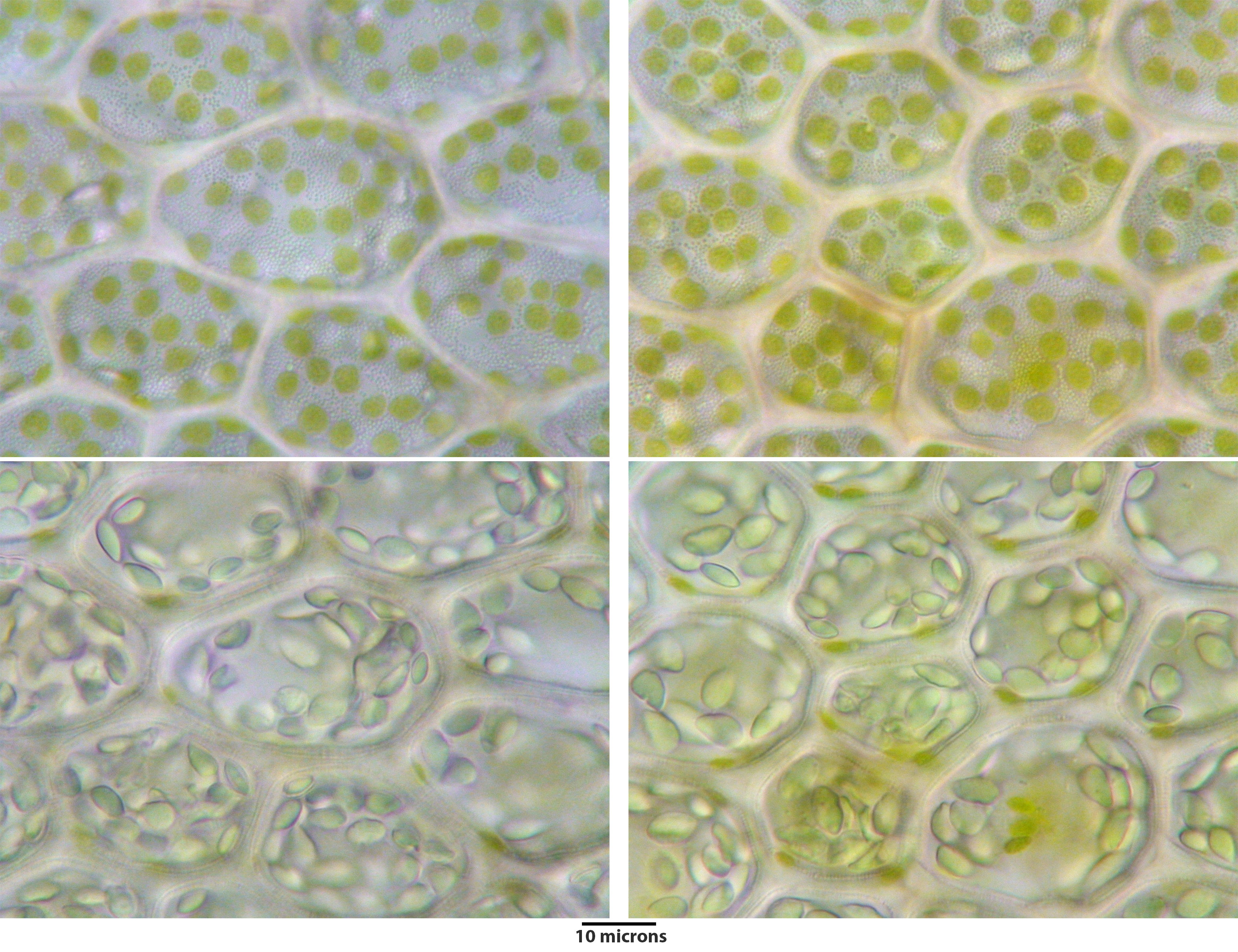

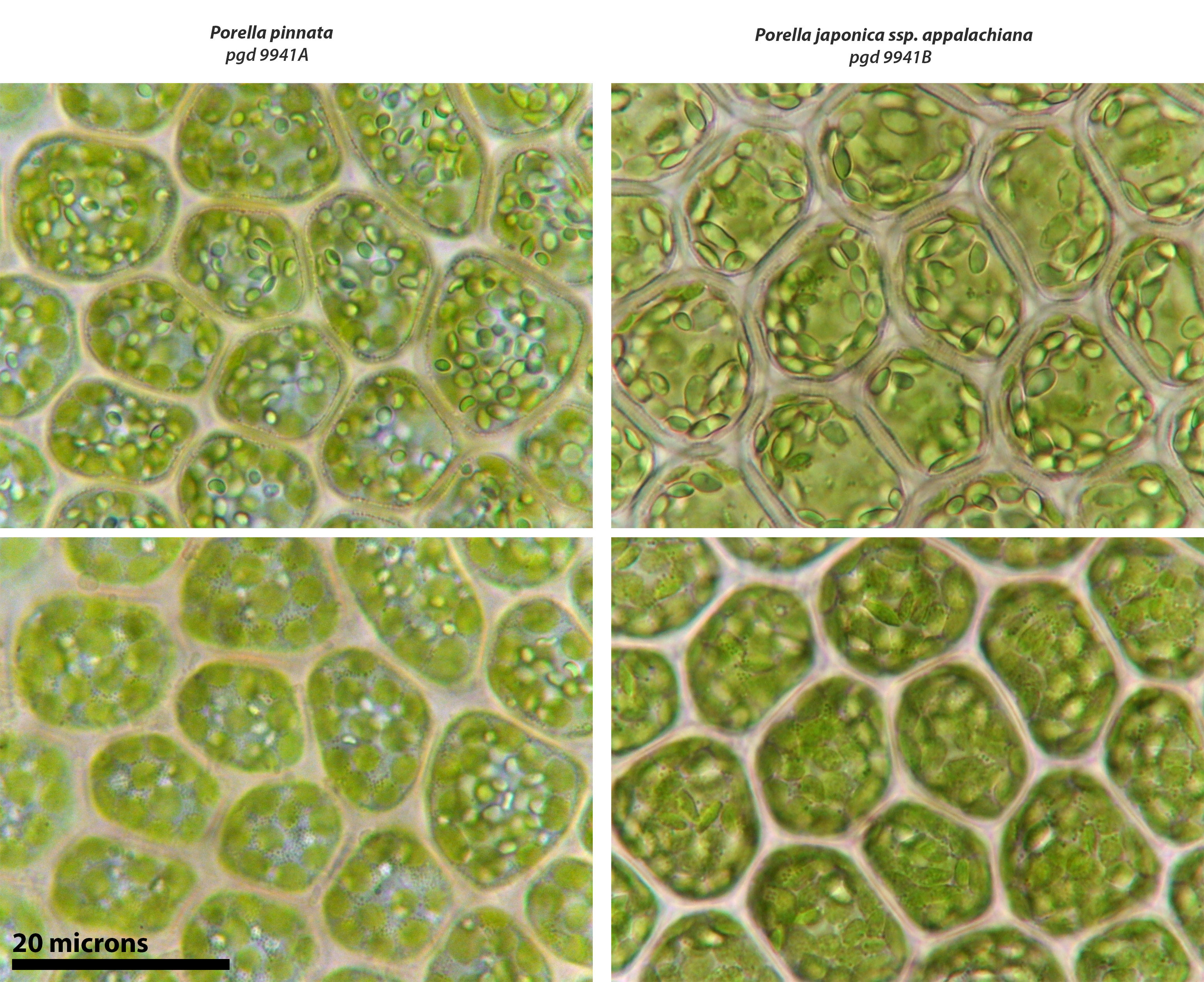

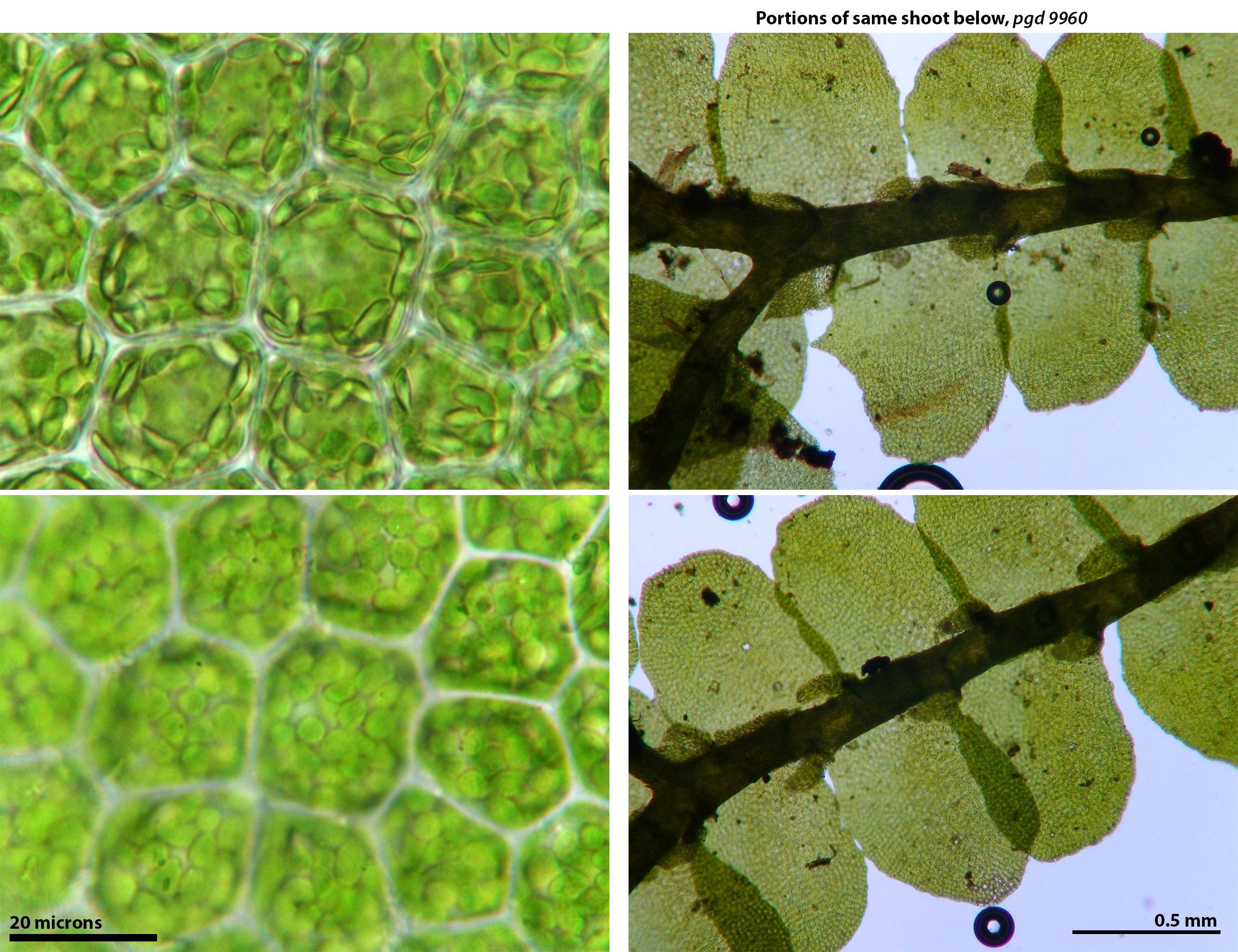

Capable of forming large mats or occurring as small strands admixed with other bryophytes. Plants bronzed (some portions may be green), shiny. Shoots 1.5-2.5 mm wide, 1 – 6 cm long, laterally branched. Lateral leaves complicate-bilobed, dorsal lobe variously toothed to entire, margins variably wavy (repand, sinuous), ventral lobe attached to dorsal lobe by a vestigial keel, ventral lobe irregularly spinose-dentate to entire, longest teeth at base of lobule. Underleaf irregularly spinose-dentate, often feebly to distinctly bilobed. Oil bodies in leaf cells as large or larger than chloroplasts.

Dioicous. Male plants occur in same gorge where the type specimen was collected. Females unknown.

In the well developed toothy extreme P. japonica subsp. appalachiana cannot be confused with other regional species of Porella. In the field well developed plants may be initially mistaken for Frullania plana, with which it may occur. The bronzed-brownish color and well developed teeth at the leaf apex suggests the discovery of an unknown species of Bazzania.

A problem lies with regional populations of essentially entire-leaved, delicate, bronzed plants, lacking circinate coiling of shoots, and with large oil bodies. Schuster (1980, p. 684) referred to such material from Crow Creek, North Carolina as potentially belonging to P. japonica subsp. appalachiana. Schuster also referred to the Crow Creek plants as “bronzed wataugensis phenotype, approaching P. japonica but much weaker” (Schuster 1980, p. 680). Hicks (1990) recognized Porella wataugensis as a distinct species found in gorges and limited to shaded rock faces never inundated. In Hick’s view, P. wataugensis differs from the ecologically similar P. japonica subsp. appalachiana in the latter’s “greater development of teeth on the leaves” (Hicks 1992, p. 131). That the type specimen of P. wataugensis was collected from a log along a river argues against applying the name wataugensis to this variable Appalachian endemic whose morphology when best developed is clearly aligned with the Asiatic Porella japonica. Most authors (e.g. Bakalin 2018, Hentshel et al. 2008, Schuster 1980) consider P. wataugensis to be a form of Porella pinnata. Schuster (1980), placed P. wataugensis in the synonymy of both Porella japonica and P. pinnata. The following sentence from Schuster (1980, p. 681) points to the difficulties: “Perceptibly complicating the situation is the fact that the variable “wataugensis” phenotypes appear to intergrade with P. pinnata fo. involuta and P. japonica.” Further study of the Porella pinnata complex sensu Schuster (1980, p. 679-681) in eastern North America is needed.

A population in Graham County, N.C. is critical in that both forms, i.e. the weaker wataugensis phenotype and the strongly toothed japonica phenotype, occur in close proximity. In some cases an organic connection between the extremes can be found (see images below). It may be that unique microenvironmental conditions of constantly high humidity and adequate light are required for the development of the toothy extreme in P. japonica subsp. appalachiana. In more shaded or less constantly humid microsites the "essentially entire-leaved" phenotype prevails.

Salient Features

- Shiny and bronzed when dry

- Leaves, at least some of the them, bearing 1-few marginal teeth

- A few underleaves slightly to distinctly bilobed

- Margin of lateral leaf lobe more or less wavy

- Oil bodies as large or larger than chloroplasts

References

Bakalin, V.A. 2018. Porellaceae. Bryophyte Flora of North America, Provisional Publication.

Davison, P. G., and Risk, A. C. 1992. Hepatics of Bad Branch Nature Preserve, Letcher County, Kentucky. Evansia, 9, 52-55.

Hentschel, J., Davison, P. G., and Heinrichs, J. 2008. Chapter Sixteen: Porella gracillima Mitt. (Jungermanniidae, Porellaceae) in Tennessee, with an Illustrated Key to the Porella Species of North America North of Mexico. Fieldiana Botany, 183-191.

Hicks, M. L. 1990. Porella wataugensis (Sull.) Howe in the Southern Appalachian Mountains. Castanea, 223-228.

Hicks, M. L. 1992. Guide to the liverworts of North Carolina. Duke University Press.

Jia, Y., He, Q., Li, F. X., He, S., Wang, M. Z., and Wu, P. C. 2016. A newly updated and annotated checklist of the Anthocerotae and Hepaticae of Qinling Mts., China. Journal of Bryology, 38(4), 312-326.

Schuster, R.M. 1980. The Hepaticae and Anthocerotae of North America East of the Hundredth Meridian. Volume IV. Columbia University Press, New York